Police unions — organizations that represent police officers — are one of the most powerful forces standing in the way of efforts to hold police accountable for violence and misconduct and to transform the criminal justice system.

Workers have a fundamental right to organize and use their collective power to ensure fair treatment and compensation. However, police unions do more than bargain for wages and benefits. They perpetuate harm, protect violent police officers, and create barriers to officer accountability and policy change.

This site exposes their playbook. From contributions to politicians, to contracts and copaganda, police unions use predictable and toxic tactics to skirt accountability for officers and block efforts towards reform. Together we can call them out on these tactics and take action to diminish the power of police unions.

In the US, there are about 18,000 police agencies, including local police, sheriff’s offices, and state police, employing about 700,000 sworn officers. With more than 350,000 members in 2,200 local chapters, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) is the largest police union in the United States — representing about half of US police officers. Many FOP lodges allow retirees to be members, and in some cities, like Philadelphia, retirees may comprise a majority of members.

Although 30% of its members are officers of color, its national leadership consists of seven white men. Many local FOP chapters and police associations are also run by white men, even in cities like DC, Baltimore, New York and Chicago, where the force is predominantly of color. The culture of white supremacy starts with leadership and trickles down.

Black officers, wanting to enjoy the power of collective bargaining for fair wages and promotions and sometimes fearing the consequences of being seen as “not-in,” often join the FOP, NYC-PBA and other mainstream police unions even as some have expressed that they’ve been unwelcoming.

However, Black officers’ organizations, such as the Guardian Civic League in Philadelphia, have increasingly stepped into the role of advocating for Black officers, creating a support network, and fighting against discrimination. Groups such as the National Association of Black Law Enforcement Officers (NABLEO) and the National Black Police Association (NBPA) have been vocal in condemning anti-Black behavior by police unions such as the FOP’s endorsements of President Trump.

Director, Los Angeles Police Protective League (LAPPL)

Elected in 2017, up for reelection this year

Business Manager and Spokesperson, St. Louis Police Officers Association (SLPOA)

Pat Lynch, President of the NYC Police Benevolent Association (PBA — formerly known as the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association)

First elected: 1999

Most recent reelection: 2015

Police unions are one of the biggest obstacles to police accountability and reform. The Police Union’s Playbook is a play by play examination of the FOP and other police unions’ tactics for protecting violent officers, creating barriers to officer accountability and policy change, perpetuating harm and maintaining the status quo of policing.

Police unions use their union contracts and introduction of legislation to negotiate contract provisions that relieve officers from accountability off the bat and shield violent police officers from investigation and prosecution.

Police unions create a public narrative that shifts blame from violent police officers to their victims, often invoking racist vitriol to absolve officers of responsibility.

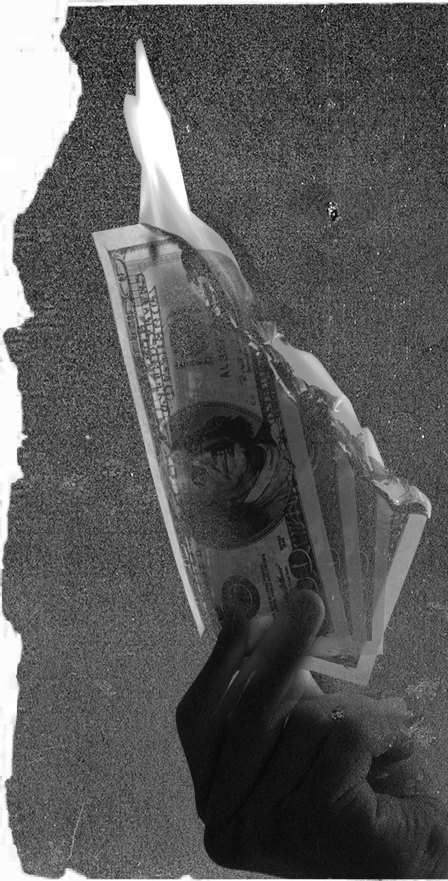

Police unions use campaign contributions to build political power at every level of government, buying influence over the way our representatives vote.

When their backs are against a wall, police unions fight back by viciously attacking champions of reform, burying their opposition in endless litigation, spending millions to lobby legislators and, when all else fails, outright defiance and neglect.

Finally, when all other tactics have failed and officers are facing charges of misconduct, police unions provide legal defense and use arbitration to shield them from investigation, discipline and dismissal, raise money to financially support these officers and push “copaganda” to absolve them from responsibility.

Page 1

Police unions use their union contracts and introduction of legislation to negotiate contract provisions that relieve officers from accountability off the bat and shield violent police officers from investigation and prosecution.

Page 2

Police unions create a public narrative that shifts blame from violent police officers to their victims, often invoking racist vitriol to absolve officers of responsibility.

Page 3

Police unions use campaign contributions to build political power at every level of government, buying influence over the way our representatives vote.

Page 4

When their backs are against a wall, police unions fight back by viciously attacking champions of reform, burying their opposition in endless litigation, spending millions to lobby legislators and, when all else fails, outright defiance and neglect.

Page 5

Finally, when all other tactics have failed and officers are facing charges of misconduct, police unions provide legal defense and use arbitration to shield them from investigation, discipline and dismissal, raise money to financially support these officers and push “copaganda” to absolve them from responsibility.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

When political opposition formed against officers forming a union, Boston police officers refused to show up to work. The Boston Police Strike was not supported by labor unions because they believed police were hostile to workers. Because Boston did not have alternative public safety measures in place that actually served the community, subsequent increases in the city’s crime rate helped drive the narrative that police forces were necessary to ensure the safety and smooth operation of cities.

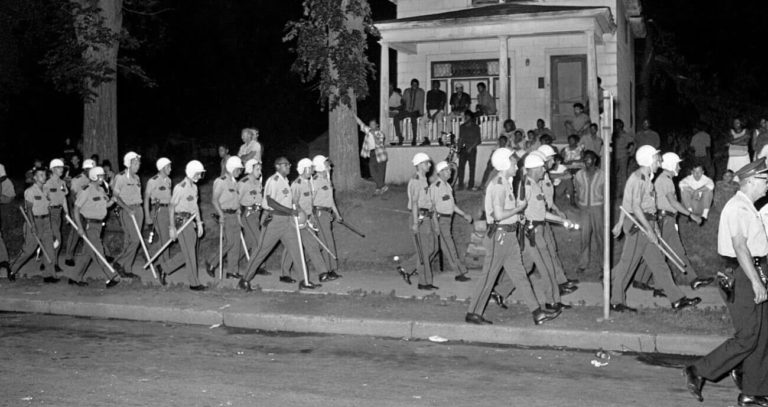

U.S. police unions, become more militant in response to early civil rights uprisings.

Police unions gained strength and became more militant in the 1960s, in reaction to early civil rights uprisings, as the Fraternal Order of Police and other unions worked to protect white supremacy and to block civil rights legislation, police reform and civilian oversight, occasionally with explicitly racist language. For example, in 1966, when NYC Mayor John Lindsay called for a civilian review board in response to widespread complaints of police brutality, 5,000 off duty NYPD cops, along with the head of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), rallied outside City Hall in opposition. They declared that they were “sick and tired of giving in to minority groups, with their whims and their gripes and shouting. Any review board with civilians on it is detrimental to the operations of the police department.” The PBA proceeded to mount a massive public relations campaign against the measure, using the threat of increased crime as a scare tactic.

By the 1970s, police unions had been so effective at diminishing systems of accountability for police officers that cops would regularly retaliate against their political targets by using violence and brute force on Black and Latinx communities if their political targets did not concede to their demands.

Flint Taylor, of In these times writes: “In 1975 in New York City, in response to proposed budget cuts that included police layoffs, the PBA ordered a rampage through the city’s Black and Puerto Rican communities, with thousands of off duty cops waving their guns, banging on trash cans, and blowing whistles for several nights until Mayor Abe Beame obtained a restraining order.”

Increases in police union membership in the U.S. as backlash to demands for police reforms and uprisings against police violence.

With the rise of of the far-right Tea Party and, later, a white supremacist in the White House, white suprmacists become even more emboldened to publicly espouse hateful and racist rheotic against Black people, and the tie between police unions and white supremacists becomes unabashedly public. In 2019, the Fraternal Order of Police and white nationalist organizations staged a protest at the office of Kim Foxx, the Cook County (Chicago) State’s Attorney, in which they rubbed photos of her over their genitals and heckled her. The union organized white police chiefs from the suburbs to denounce Ms. Foxx at a news conference while.supporters of the police forced a member of her staff to go on leave by harassing her with phone calls, berating her as an “N-word whore.”

The Brennan Center has documented widespread white supremacist infiltration of law enforcement, in more than a dozen states, while hundreds law enforcement officials have been caught expressing racist, nativist, and sexist views on social media, such as a police officer in Muskegon, Michigan who displayed Confederate flags and a framed KKK application in his home.

According to police observers, recent increases in police union membership in the U.S. are a backlash to demands for police reforms by the Obama administration and recent uprisings against police violence. Researchers have recently documented at least 24 instances of police who had worked openly with white vigilante counter protesters.

Police unions defend officers accused of racist behavior. And while collective bargaining is still banned for police officers in Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and limited in Texas, those police unions still exercise a huge amount of power.

Jamie McBride, a Director of the Los Angeles Police Protective League (LAPPL) for the last six years, has spent 30 years in the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), which has a shocking history of racial profiling, violence, and other serious systemic internal problems. As an officer, McBride racked up a disproportionate number of on-duty shootings and fought efforts to discipline officers and foster officer accountability. The Los Angeles Police Protective League and McBride embody a culture of bypassing accountability and rewarding officers who engage in racist and dangerous behavior. McBride has been a resolute voice for the police union in response to public outcry around charges of police brutality and racism and has been known to refer to Black Lives Matter as “an anti-police hate group” and a “modern-day Black Panther type of organization.” Under McBride’s leadership, the LAPPL has successfully supported measures that undermine police accountability, such as Measure C which allows officers accused of wrongdoing the choice between appearing before a disciplinary board staffed by police leadership or an all-civilian review board, defended the actions of officers who have been found to have acted in violation of LAPD policy, and donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Los Angeles City Council candidates with the aim influencing the city’s decision-making processes and $1 million to oppose progressive prosecutor George Gascón. The LAPPL also supports policies from the death penalty to increased incarceration and harsher sentencing.

Jeff Roorda is a former member of the Missouri House of Representatives and the current business manager and spokesman for the St. Louis Police Officers Union (SLPOA). A former police officer, Roorda was fired for misconduct, making false statements, and filing false reports. SLPOA has protected and rewarded other officers regardless of their conduct: In 2011, the SLPOA paid the bail of Jason Stockley, the officer who shot and killed Anthony Lamar Smith, and, in the aftermath of the 2014 murder of Michael Brown, the SLPOA was publicly supportive of Minneappolis police officer Darren Wilson with union members sporting “I am Darren Wilson” bracelets. The SLPOA has also led opposition efforts against reform prosecutors and fed racist flames through referring to Black Lives Matter activists as thugs and spearheading racially fueled attacks on Black public officials, such as Tishaura Jones and Kimberly Gardners. The racist culture which underpins the union’s actions is further exemplified in the SLPOA’s leadership urging officers to adopt the Punisher Blue Lives Matter symbol on social media, a symbol adopted by white supremacists.

Pat Lynch, a public Trump supporter and the long time president of the NYC PBA, has cemented his decades of support from the city’s largest police union through actively rejecting rule changes and efforts to promote transparency in police disciplinary processes and opposing attempts to increase officer accountability. Under Lynch’s leadership, the PBA tried to stop a state law that makes officers’ disciplinary records public, opposed bail reform, and tried to stop a ban on chokeholds. In the wake of 2020 protests, Lynch has attempted to increase the political power of the PBA through fomenting hysteria about crime, saying, “Our city needs to wake up to the fact that our leaders have surrendered the streets to chaos” and ‘I’ve never seen our streets go this bad so quickly.” He’s managed to further leverage his political power in NYC by rescinding endorsements of New York politicians who donated to police, but have spoken out about the need for police accountability.

Bob Kroll is a public Trump Supporter with a long and controversial history. He has repeatedly referred to Black Lives Matter as a “terrorist organization,” and has been the subject of numerous lawsuits including a 2007 racial discrimination lawsuit brought against the Minneapolis Police Department by five long term Black officers, and a lawsuit in which it is alleged that Kroll beat, choked, and kicked a 15-year-old biracial boy in the groin while spewing racial slurs. Bob Kroll, who is stepping down, has been known to sport a White Power Patch and engage with groups, such as City Heat, which routinely display white supremacist symbols. With Bob Kroll at the helm, the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis (POFM) sold “Cops for Trump” T-shirts on its website; undermined the public’s safety through facilitating an exclusive partnership to offer every officer in the union the banned “warrior” training — referred to as “killology” — for free; and publicly offered full support to the officers who killed George Floyd. Opposition to police accountability measures predates and transcends Bob Kroll’s leadership, operating as a foundational value. For example, in 2007, POFM successfully petitioned the Minneapolis City Council to curtail the power of the Minneapolis Civilian Review Authority by shielding from public view findings of officer wrongdoing and misconduct. Law enforcement agencies have been unable to discipline and remove bad officers from patrol or to implement clear criteria on the use of force and de-escalation, as evidenced by court documents, stalled state legislation and a U.S. Justice Department report.

John Catanzara Jr., a long time officer with the Chicago Police Department, was elected as the President of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) in 2020, after being stripped of his police powers and while being investigated by internal affairs. Catanzara’s career with the Chicago Police Department is defined by at least 46 misconduct complaints and seven suspensions, making him one of the most disciplined officers in the Department. On social media, Catanzara has also made racist and mysogynostic social media remarks which target women and Muslim people, among others. Catanzara’s successful rise to President is indicative of the Chicago FOP’s long history of supporting or rewarding officers who pose clear threats to the public and stonewalling reform. For example, the Chicago FOP helped fund the appeal of the Chicago police officer convicted of the 2014 murder of Laquan McDonald. In recent years, the Chicago FOP has supported Trump, made right wing alliances, obstructed reform, and targeted progressive prosecutor Kim Foxx and Mayor Lori Lightfoot with aggressive public efforts, like using racist rhetoric and organizing a march on Foxx’s office with identfied hate groups — like Proud Boys and the American Identity Movement — by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Catanzara himself vocally supported the January 6, 2021 insurrection. He has also threatened to kick fellow officers who kneel or show sympathy to protestors of police violence out of the FOP.

John McNesby, a member of the Philadelphia Police Department since 1989, was elected president of the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) in 2007. Under his leadership, the city’s largest police union has engaged in acts such as selling shirts in support of a police commander charged with assaulting a protester at a demonstration and has consistently been marred by numerous reports of its officers supporting white supremacist groups such as the Proud Boys, and engaging in racist social media posts, message boards and Twitter. McNesby has been quoted referring to Black Lives Matter as a “pack of rabid animals” and “a racist hate group.” On top of this, McNesby has engaged in disturbing displays of racism such as organizing a “Back to Blue” rally in direct response to growing outrage in the city following a Philadelphia police officer’s fatal shooting of unarmed black man David Jones.